The Case for Non-Universal Chains

Understanding the Evolution of Crypto Networks

Marc Andreessen said years ago that software is eating the world. The metaphor was perfect: flattening, crushing, and transforming social life into a uniform substance for investors to digest.

Today the world is fighting back under the banner of “plurality.” The world doesn’t want to be a uniform substance — it wants to be many things, many sites of power, many communities, many ways of thinking.

The push for plurality, however, is not “web3 versus the old world.” It’s more like an internal struggle for the soul of the new decentralized web, against the totalizing mentality that dominated web2.

In this piece, we explore the theme of money and power. How has money, in the past, tended to erode plurality and concentrate power? Blockchain technology gives us a rare opportunity to rethink all of this, so let’s get it right. If the new monetary institutions we’re building are to preserve and strengthen plurality and community, what will they need to look like?

We start by talking about money’s relationship to power and information. We move on to talk about what more pluralistic money might look like. Take note of where cryptocurrencies and blockchains currently stand in the process of dislocating old power structures, and offer some ideas for steering the space in an attractive direction.

1. Money as a share of the police power

The Sorcerer’s Apprentice, a parable about summoning uncontrolled power, is a nice lens through which to understand the wizardry of money.

In the beginning our young apprentice (Mickey Mouse) has a broom — an inert tool. But when he puts on the sorcerer’s hat, he transforms that broom into a sentient being. What was once a broom becomes something other than a broom.

Money too is a shapeshifter. Every textbook will tell you so: it’s a medium of exchange, but also a store of value, and a unit of account. Most people don’t quite grasp the strangeness of this. Money is not one thing with multiple uses, like a broom that doubles a toy horse. It really is several radically different things, depending on its context — more like Mickey’s broom and the living broom-creature.

In its medium-of-exchange form, money is simple, like Mickey’s inert broom. Basically anything can be a medium of exchange, which is why barter works. Yes, things that are light and divisible facilitate exchange better, just as objects with long handles and brushy heads sweep better. But exchange is a fairly prosaic function.

Transforming money into a store of value, however, requires sorcery. How else could worthless paper, or handfuls of seashells, store vast power?

When the broom comes to life, an unseen power animates it. The same is true with money, but here the unseen forces are not magical. Peering behind the curtain, what animates money is power. In the world in which we find ourselves, not all but much of that power is police power.

Why is police power so important? Money is only as valuable as what it buys, and in a world without police power, there wouldn’t be as many powerful things to buy. You couldn’t buy land, you couldn’t buy contractual rights, and you couldn’t lend money at interest to people you didn’t trust. (The last two assume no smart contracts of course, which we’ll get to soon.)

So on this view, money-as-a-store-of-wealth is like mana directing the state’s police power. The wealthy purchase enforcement privileges, known as property rights, that the state has released onto the market. People’s net worth in money, minus a constant for universal rights, thus measures what their country is willing to do for them, relative to what it will do for other people.

Money has always been issued by coercers: kings, conquerors, and other warlords. Marco Polo introduced European readers to paper currency by describing how the iron-fisted Kublai Khan used it to extend his power. The Khan required merchants to use his paper in exchanges between themselves, and required would-be exporters to his kingdom to sell him goods in exchange for it, making him almost infinitely rich.

Warlords issue money to keep track of their transferable debts. Because the money comes from the warlord’s printing press, having a lot of it is evidence of having conveyed value to the warlord, directly or indirectly. And warlords repay their debts with physical protection and privileges. An economy structured around the pursuit of a particular currency is, in a way, structured around the pursuit of its issuing warlord’s good graces.

This is the spell by which money transforms from something inert, a medium of exchange, into something animated, a store of value. More than mere grease for transactions, money’s ability to buy a share in dominant coercive powers brings it, for better and worse, to life.

2. Money as a Universal Language

The sorcery of coercion stirs the broom to life. But money truly becomes a fearsome golem when it assumes the form of a unit of account — that is to say, a language in which all other things’ value is expressed.

We are so familiar with money playing this role that we hardly even notice it. But we don’t necessarily need any single money-like variable by which to measure everything’s value. Without one, people needing a house would think about value in terms of houses, people needing food would think about value in terms of food, and people needing social belonging would think about value in terms of belonging.

We already do this privately. We privately interpret the value of money in terms of how much of what we want it can buy us. But publicly, we use money to communicate about value, because we know that different people understand money’s value reasonably similarly, despite vastly different situations regarding particular goods like food, or houses, or social belonging.[1]

The fact that money’s value draws upon police power also explains why it is so effective as a universal language of value. Regardless of the huge differences in our needs for particular things, every human being in a tightly-policed society is in fairly dire need of the police being roughly on their side. And in societies like ours — racism notwithstanding — having wealth and purchasing property is the clearest route to achieving this. This is so obvious and visceral that it makes money a near-universal language of value: a common unit of account.

3. Breaking Down Money’s Problems

The question of how to improve money is complicated by the fact that it is three things, not one. But let’s break it down. We should question whether we truly want money to play the three roles it plays, and if so, how it could do those jobs better.

Money’s first face, as a medium of exchange, is its least troubling. After all, trust and friendship also facilitate transactions, to no one’s great alarm. Some may fret that money reduces the need for trust and friendship by letting commerce happen without it. But to the extent that trust and friendship depend on transactional imperatives, they probably don’t deserve to be called trust or friendship anyway. There’s more than nothing to worry about here, but even bigger difficulties arise with money’s other two guises.

Money’s second face, as a store of value, is worth questioning. Surely we want certain means of storing value across time so that we aren’t always rushing to offload it. And promises to coerce do store value efficiently, as long as someone stands willing to enforce them. But storing value is not an unvarnished good, because keeping value flowing is at least as important as storing it. When it is easier to warehouse value risklessly, the wealthy have less incentive to productively deploy their resources. There is a complex tradeoff here.

Money’s third face, as a unit of account, is even more dubious. There are obvious benefits to having a universal language of value: it widens the circle of people with whom we can trade, and so maximizes the potential for gains from trade. But this comes at a steep cost to community and plurality. It encourages everyone to think of their relationship with the power behind money — e.g., the police — as more important than their relationships with their communities. By extension, this causes people to consider what is valued by the vast, unwieldy set of people that use a particular kind of money — we might call this a currency community, although it doesn’t really have any features of a normal community — instead of considering what is valued by the people around them, their real and proximate community. Here is where money interferes with trust, solidarity, and human relationships.

This is more than just sad. It is also inefficient. Because everyone is in a better position to understand and serve the needs of their proximate community than the whole vast and global currency (non-)community. In short, universal units of account encourage us to transact (though not necessarily form real relationships) with people distant from us. And they distract us from people close to us.

Before moving on let me rebut an obvious objection: Isn’t it miraculous and good that money lets us collaborate with people distant from us? Yes! A world where impersonal, long-distance economic collaboration were impossible would be much worse than the world we have. The problem, however, is that conventional money makes it equally easy, or indeed even easier, to collaborate with people far from us, compared to people close to us. To the extent that we interact with members of our communities through the lens of such a tool — which, again, puts people outside our community on exactly equal-or-better footing — we actually don’t have a community anymore.[2] By contrast, you can imagine a world in which money preserved thoughtful gradients between communities, emerging along any many axes, so that impersonal and distant transactions, and/or removals of capital from communities, were comparatively costly. Picture a global economic network, but one richly textured with emergent structures, instead of a flat, unidimensional, faux-neutral one. This is the sort of thing I have in mind.

4. Cryptocurrency

Cryptocurrencies and blockchains present us with an opportunity to put money, and the power it represents, on a different foundation. This could go well or poorly. Recall that we are only doing our best here to talk about something wildly complex. Many different futures are possible. But try carrying this lamp into the wilderness: the good futures for blockchains and money are less fundamentally univeralistic than the status quo, while the bad futures are more so.

Let’s begin by dismantling a major red herring: decentralized architecture cryptocurrencies’ value from the police power. Like any other money, decentralized cryptocurrencies’ value depends on from what it can buy, and their advent has not diminished the array of buyable property interests like land and legal contracts. These are still protected by ordinary governments with guns, cuffs, and jails. Kublai Khan is still Kublai Khan, and all petty lords remain dependent upon his might.

So how might these technologies actually put money on different foundations? Let’s consider a possible sequence of dislocations of power, and then imagine what might fill the voids left by these dislocations.

The first dislocation, which we’re already seeing, is simply that Kublai Khan (i.e., the state) is no longer the only money printer. It is now possible for anyone to generate tokens and use them in exchange. Thus, if you buy a property right with a cryptocurrency, you’re buying a share of the Khan’s police power, but not using the Khan’s currency. This does not by itself alter the state’s role as the dominant coercive force, but it does diminish its ability to multiply and extend that power by printing money.

The second dislocation, which has begun but is still very early, is where decentralized architectures offer alternatives high-level, state-like institutions and infrastructure. DeFi is in the early stages of mounting a challenge to capital allocation and banking (which are, of course, are extremely state-adjacent functions). Handshake (for internet domains), DexGrid (for electrical grids) and many other projects are providing state-like infrastructure, both digital and physical. In the future, we might also imagine decentralized dispute resolution becoming preferred to traditional courts, and decentralized certifying networks assuming the mantle of state regulators. This might sound dramatic but it would not be very shocking. After all, clunky institutions like the American Arbitration Association already manage huge swaths of commercial interactions in the United States; these could be outperformed by decentralized networks. And of course many politicians would jump at the chance to outsource regulatory apparatuses.

What about “sensemaking”? We might imagine decentralized verification networks attesting and certifying the authenticity of documentary evidence. If deepfakes become pervasive, and journalism becomes further politicized, you’ll need decentralized human attestation networks to be able to trust evidence you didn’t gather yourself.

The third dislocation, which has not yet begun, is where new systems begin assuming the most basic tasks of states: protecting the power of the rich and the health of the poor. Here, it’s helpful to think of decentralized architectures as simply facilitators of mutual aid. The rich will need state police less if they are able to use new networks to better secure their property. And decentralized mutual aid networks might in the not-too-distant future provide more meaningful assistance to the poor than state programs.[3] Private networks may also soon begin backing currency with state-like power over information.

In other words, decentralized networks are beginning by contesting state power’s most abstract functions, such as money printing, capital allocation, and digital infrastructure. But they are gradually pushing towards foundational, ground-level state services.

At every level of this contestation, there are opportunities and dangers. The opportunities are clear enough. We’d all like things to work better than they do; and the possibility of a more diverse and regenerative world is quite real. But we should also name the danger so that we can avert it. Let’s make damn sure that the new structures aren’t even more unidimensional and illegitimate than the flawed old ones.

5. Loose Ends

a. The Voids of Dislocated Power

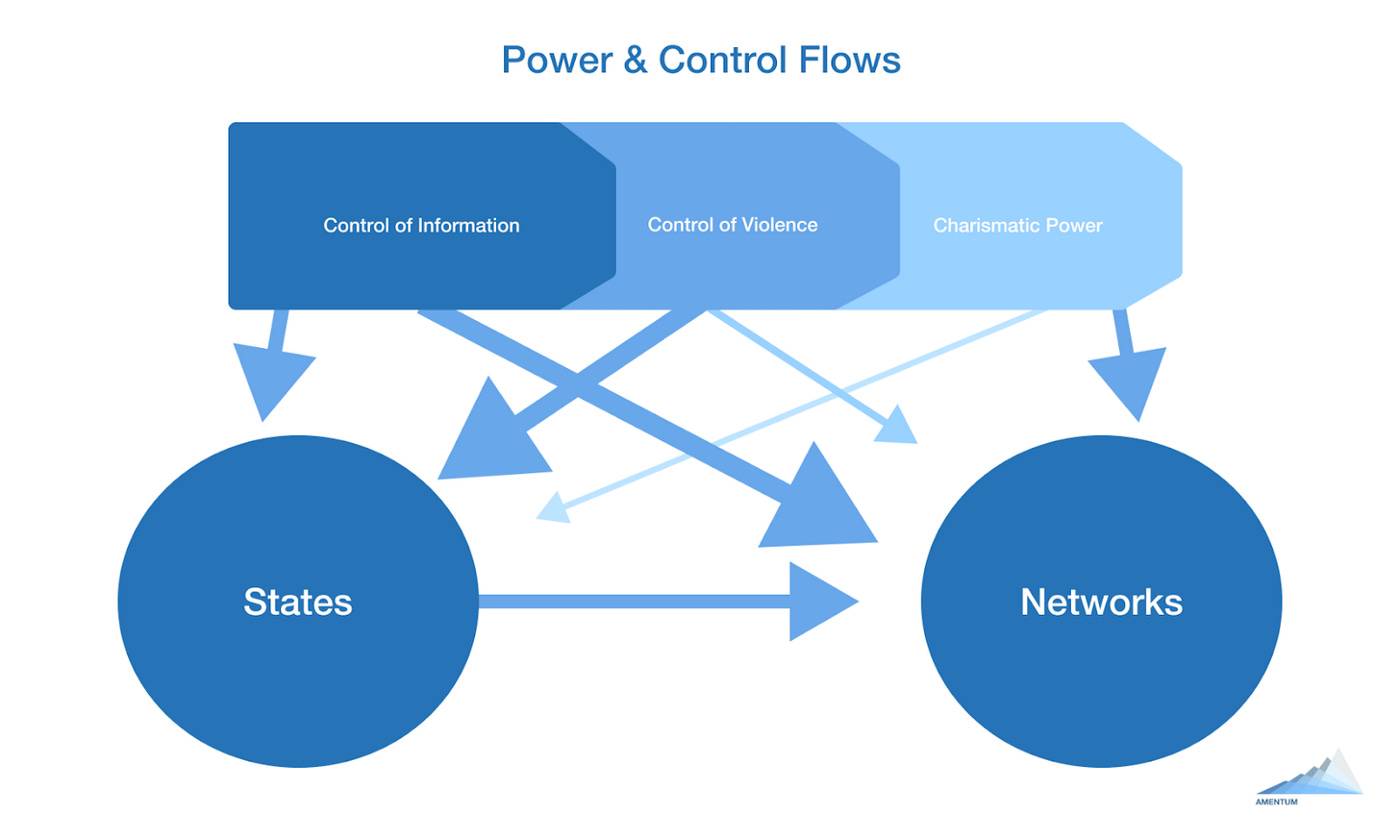

In the book “The Dawn of Everything”, David Graeber and David Wengrow usefully put power in three categories: control of violence, control of information, and charismatic power. One way of thinking about new network technologies (including blockchains, but also other new structures like federated data networks) is that they create new amalgams of power that challenge older ones, including states and corporations.

These networks enable deeper forms of cooperation and information swapping, with less reliance on police assistance in the form of contract enforcement, etc. One of the reasons they work is that power within them can be linked to secret, private keys. Thus, pre-programmed arrangements can be carried forward without needing anyone to keep peace in the union hall, so to speak. A new degree of control over information enables new cooperative arrangements.

b. Whose Charisma?

As we’ve said, some of the value flowing through blockchains depends on violence. But some such value depends on shared belief in a story, which we might call charisma.

We think it is in this realm of charismatic power where the greatest opportunities and hazards lie. The fact that a system of secretive and diffuse charismatic power may soon outperform a system of coercive power in facilitating coordination gives us a chance to build something better. But whether it really is better depends on the character of the story we believe about where value comes from.

There are two charismatic stories we might accept going forward. One says that value is universal: that we can and should all embrace a common unit of account, so that our subjective valuation of everything should correspond to the globally highest bidder’s valuation of that thing. (The global economy already almost works this way, but cryptocurrencies could pave the way toward an intensification of that universality. See, e.g., Bitcoin maximalism.)

Another story says that this is nonsense. The global highest bidder for a thing, in dollar or Bitcoin terms, is likely to have no relationship to you. Selling by default to that bidder thus ignores the probable positive externalities of transacting within your community (geographic, familial, socio-cultural, or otherwise). These externalities are inherently hard to assess, but global units of account are essentially a set of blinders engineered precisely to ignore them.

What if we saw our communities as the true sources, guarantors, and yardsticks of value? With a greater diversity of currencies and a new perspective on what they mean, this is eminently possible.

c. And, Taking Property Off Of Its Coercive Foundations

The matter of violence still remains. Reexamining the nature of property itself, and making coercive property privileges non-buyable, is a related and complementary area of work in putting the economy on new foundations. Here too, we can imagine technology opening new vistas.

What if, for example, we bundled real-world property rights into NFTs governed by partial common ownership, that funneled rents back into community? But that’s for another piece.

d. Blockchain Non-Universalism

It seems clear enough that the kind of economic structures envisioned here — richly textured, community-oriented systems of exchange and value creation — will depend on communities’ ability to create quasi-distinct ecosystems that nonetheless talk to each other when appropriate. In other words, we believe in a world of many chains interacting in a structured way. Connext is a leader in building infrastructure with this shape, and it’s one of the reasons we’re so excited about it.

These distinctly modularly and separate layered ecosystems are providing utmost redundancy and resiliency as they continue to command developer recognition and liquidity. The architecture of systems, such as Connext Network, allow us to envision a more adept attempt at creating seamless cross-connectivity between these emerging ecosystems; while the inherent technical modularity creates a seamless feedback loop of incentives and community cross-pollination.

6. Conclusions

Money draws on power. And new networks are reconfiguring the pool of power from which money draws. To make the future better than the past, we’ll need to make sure that the new reservoirs of power are more, not less democratically accountable. There is no guarantee that this will happen — it’s a vision that needs to be fought for. But if it does, the economy will look more like biology: countless richly textured emergent economic substructures, blooming in a vast garden. It will look less like machinery or monoculture — it will not be a single currency, a single blockchain, a single regime — no single way of living “eating the world”. Let’s work toward that, together.

[1] Of course there are also some limits to how similarly we understand the value of money, illustrated by one of the better jokes in sitcom history, when an out-of-touch wealthy character in Arrested Development wonders dismissively: “What could a banana possibly cost? Ten dollars?”

[2] For a deeper dive on what I mean by “community” — a big topic necessarily elided here — see e.g. Ronald Dworkin on associative communities in Law’s Empire (1986). “If we felt nothing more for lovers or friends or colleagues than the most intense concern we could possibly feel for all fellow citizens, this would mean the extinction not the universality of love.”

[3] The fourth step in this sequence would involve the military, the state’s external power. We’re much farther from this, so let’s leave it aside for now.

Very helpful walk through the facets how money interacts with humans! It was almost a bit surprising to transition to the key role of cross-chain communication in the later sections, as so much of the article talked more about "community" in the geographic sense. But after thinking about how even for the small set of community types examples "geographic, familial, socio-cultural, or otherwise" interplays with value capture and sharing in community types, it starts to become clear. The key is in what is different about the value system inherent in a bitcoin, say, compared to GTC or even, more differently, FIL, where the economy, purpose, and value of the community around those two has a purpose quite different (in useful ways) than that of BTC.

Great stuff. Would also be curious what a “decentralized force” would look like or be formulated? I imagine like most militia/guerrilla forces that have come before but they where driven mostly by the ‘Charismatic’ incentives of an ideology or leader.

What’s Guillotine DAO gonna look like?